Fake News Along the Santa Fe Trail

Posted on August 5, 2019, by Loretto Community

By Susanna Pyatt

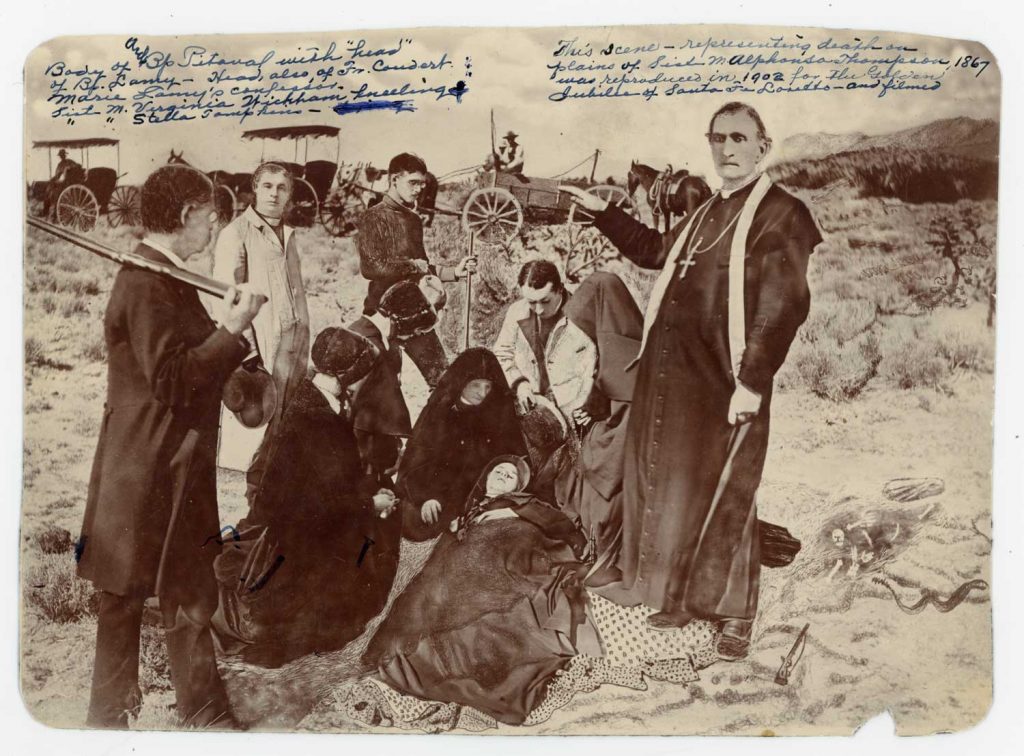

In 1867, three Sisters of Loretto – Sisters Kostka Gauthreaux, Alphonsa Thompson, and Isabella Trealler – set out from Kentucky and Missouri to follow the Santa Fe Trail to New Mexico. There they would join other Sisters in the growing work undertaken by Loretto in the American Southwest. The three Sisters traveled with a caravan including Bishop John Baptist Lamy, European clergy and seminarians, and two Sisters of Charity of Cincinnati. For part of the Trail, they also joined with a larger, armed caravan. The hardships of travel included bad weather, rough trails, raids by Native Americans, and disease, including the illness that claimed the life of Sister Alphonsa.

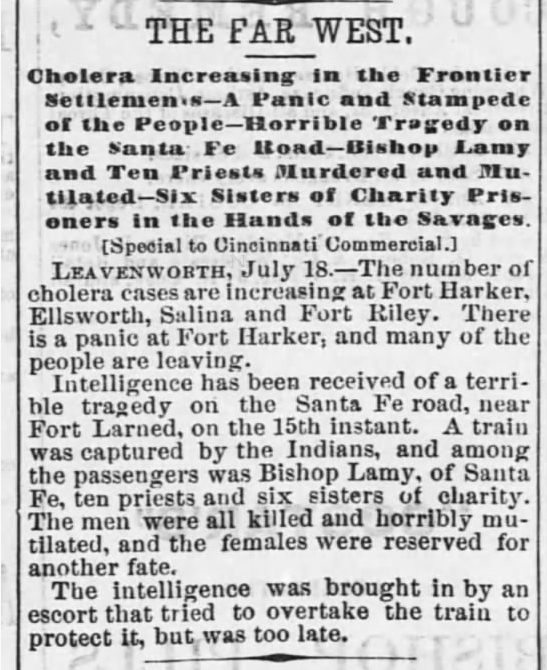

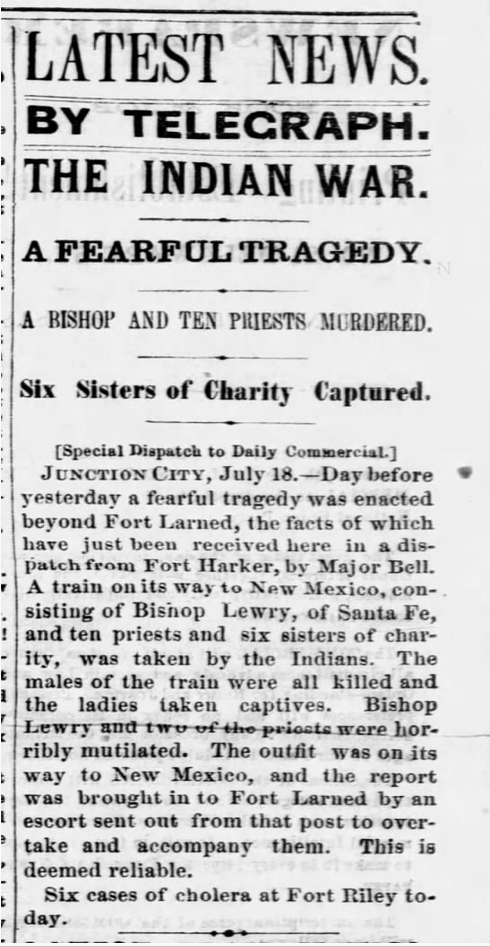

As they traveled, their journey was notable enough to gain national news recognition – but not for anything that actually happened to the caravan. “A Massacre on the Plains,” read the headlines. “A Fearful Tragedy,” “Indian Outrages: Capture of Another Train!,” and “Horrible Tragedy on the Santa Fe Road” were other captions. Newspapers from California to New York City and as far away as Scotland reported that Native Americans had murdered and mutilated Bishop Lamy and his fellow clergy. Not only that, but six Sisters of Charity had been captured. Some stories added an additional note of tragedy, that an armed escort had been on its way to protect the caravan but arrived too late to do anything more than report the massacre.

Clippings from the Leavenworth Daily Commercial (July 19, 1867) and the Daily Ohio Statesman (July 20, 1867). Courtesy of newspapers.com.

Clearly, the newspapers had the facts wrong, from the event of the massacre to details such as the numbers of religious in the caravan, which congregations they belonged to, and Bishop Lamy’s name. Historian Alice Anne Thompson traces the first publication of the false story to the July 16, 1867, issue of the Junction City, Kansas, Union.1 The story was widely published on July 19 and successive days. By July 22, however, newspapers were also publishing corrections of the story, having received word that it was fabricated.

Around the time of the story’s first publication, the travelers learned of the false tale. Jesuit priest Donato Gasparri recorded in his account of the 1867 trip that “at Fort Dodge the news had come that we were attacked and our caravan destroyed except the religious women who had been taken as prisoners. This news was relayed to the Secretary of War in Washington, and from there on to Europe.”2 But the members of the caravan probably had more pressing concerns at that point than correcting the news story, as they were facing the fatal illnesses of several of their fellow travelers and had suffered actual raids.

Like incidents of fake news today, the false reports of the massacre of the party played to fears and politics of the time. The American West was in the midst of the Indian Wars; in some newspapers, the brief description of the “massacre” of Lamy’s party accompanied the (truthful) notice that the bodies had been found of Lieutenant Lyman Kidder and his men, who had been killed in a fight with Native Americans on July 2. The story of Bishop Lamy and his caravan was even more sensitive, involving an attack on unarmed men of God and pious, virginal women. While most of the news reports wrote only that the Sisters were captured, others phrased it as “abused,” “outraged,” or “reserved for another fate.” That fate must have been considered truly worse than death for the Sisters, as one account of their 1867 trip recorded that specific men were assigned to shoot each Sister if their caravan was to be defeated in a raid.3

A few newspapers published political commentary on the occurrence of the supposed massacre. The Brookville Republican in Pennsylvania printed a call for the construction of western railroads, connecting them to the spread of civilization: “It is useless and puerile to bewail or grow sentimental over special horrors, be they ever so bloody, when we have within our own resources the power to crush out peacefully and forever the barbarism that produces them.” The Woodstock Sentinel in Illinois took a more violent approach: “The prompt and efficient action of the Government and the military authorities for the protection of the routes of travel upon the Plains, and the punishment of the ‘red-skin’ miscreants, is demanded.”

Such fear-mongering and political effects of such fake news were noted at the time. General William Tecumseh Sherman commented directly on the fake news report, citing evidence against the massacre having occurred and writing that “The country has been shocked by so many terrible accounts, fabricated for a purpose…that, I think, journalists should endeavor to ascertain the truth before shocking the public with such terrible announcements.”5 Others were even more direct in calling out the political motives behind such false reports. An article printed in the Philadelphia Evening Telegraph decried the “dishonest speculators” profiting from the Indian Wars and circulating fake news because “There is nothing they dread more than peace. There is nothing for which they scheme and maneuver and lie so eagerly as for a good long, bloody war.”

The long travel, raids, and disease not withstanding, Bishop Lamy’s caravan made it to Santa Fe on August 15. On their arrival, the clergy and Sisters were richly welcomed with processions – and also sadness, as some of the travelers had not survived the trek west. Bishop Lamy concluded his published report of the trip by saying the Sisters “are agreeably disappointed to find here flourishing establishments with more commodities than they expected to see with adobe buildings.”6 Loretto institutions were flourishing in New Mexico in 1867, and the Sisters would continue to spread their work in the Southwest over the next decades.

Notes

1 Thompson, p156.

2 Account of Donato Gasparri, transcribed by Sr. Lilliana Owens, SL. Loretto Heritage Center collections.

3 See Thompson, p138-141.

4 See Thompson, chapter 25.

5 See, for instance, Leavenworth Times, July 23, 1867, p1.

6 See, for instance, Buffalo [New York] Commercial, September 10, 1867, p2.

Additional Reading

Patricia Jean Manion, SL, Beyond the Adobe Wall: The Sisters of Loretto in New Mexico, 1852-1894 (Two Trails Publishing Press, 2001)

Alice Anne Thompson, American Caravan (Two Trails Publishing Press, 2007)