Only One Heart: Loretto and Indigenous Peoples

Posted on October 4, 2020, by Loretto Community

“As we grow in trust through friends gathered around the table, we are learning how God takes our time and makes it sacred.”

Trappist Father James Behrens OCSO

Loretto still stands at the borders along the tribal lands, remembering our presence there in the past century to now. How much we have learned from our ancestors on the land where they were first. We hold on to all the blessings.

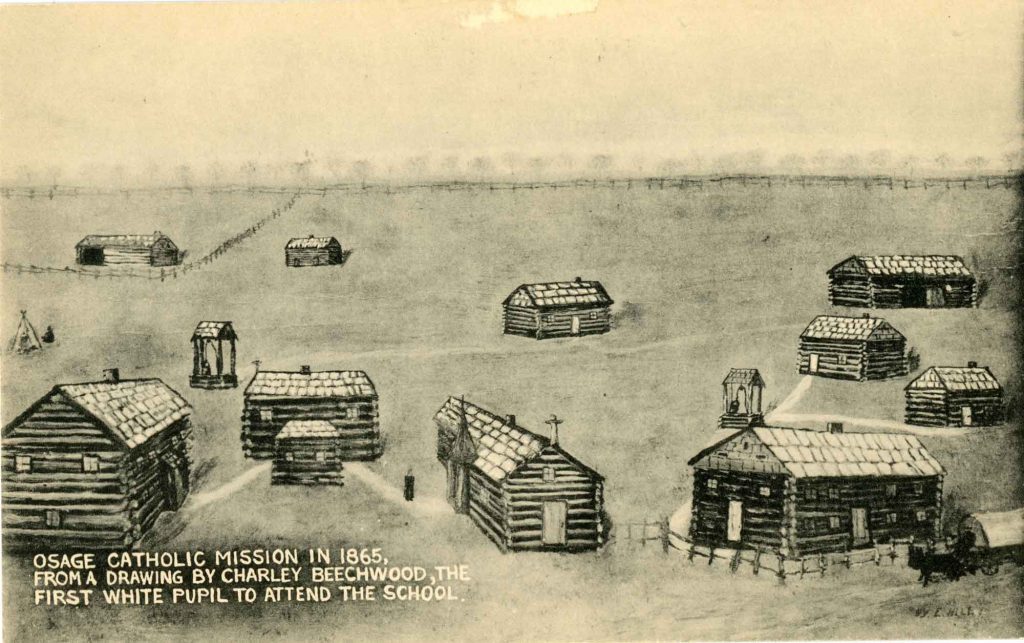

In 1847 the Jesuits opened a school for members of the Osage tribe in Osage, Kan. Soon it was realized that the girls of the tribal families needed the same education. Father John Schoenmakers SJ set about the difficult task of finding a group of religious women to run his girl’s boarding school. In St. Louis he talked to several orders of nuns. None were willing or able to go. Discouraged, he traveled to Kentucky to visit the Loretto Motherhouse in Nerinx. The Sisters of Loretto were receptive to his call because of their long respect for their co-founder Father Charles Nerinckx, whose desire was that they work with the Osage. Their ranks included sophisticated, well-educated young women who had vowed to serve the missionary works of God. On Oct. 10, 1847, Father Schoenmakers returned to the mission with Mother Concordia Henning and Sisters Bridget Hayden, Mary Petronilla van Prater and Vincentia McCool. The Osage School for Girls opened on the day of their arrival.

The mission functioned precariously. The nine Jesuit and Loretto missionaries were among few white people in the region, and all but one of them were immigrants. Kansas was not yet a territory, and statehood was 14 years in the future.

In Loretto’s early history working with Native Americans, while we thought of our work as mission, that work came about through a contract with the U.S. government to operate boarding schools on tribal lands. We now more fully understand that the government’s purpose to contract such work was in connection with its efforts to pacify Indigenous Peoples. In 2017, some members of the Osage people from the tribal center in Oklahoma who visited our Archives in Nerinx, Ky., helped us to understand that their community lost contact with their own youth in the 25 years or so that followed Loretto’s opening and operating the Osage Mission school. We acknowledge that while Loretto’s intent was to try to do good then, from the vantage point of what we know now, our efforts are seen by some as highly problematic. It also must be acknowledged that Loretto has never wavered in recognizing the interconnectedness of all peoples. Living among Indigenous Peoples deepened our connections to Earth’s gifts. We will never erase our memory and common bonds.

The beauty of the plains and the desert accompanied the friendship of the people who lived there centuries before Loretto searched for belonging. “Welcome,” they said. “Welcome.” What Loretto learned was nourishing. It shaped our identity and teaching. We wondered at the exchange of learning. We were vulnerable to be open to the new and beautiful cultures.

Our long history in the Southwest called for partnerships and new collaborations. We learned so much. We were changed by our friendships with the Native communities. Our spirituality was deepened by those human experiences, and we are thankful for new paths to God.

According to “I Am the Way,” Loretto’s Constitutions, the spirituality of Loretto directs members to praise and to minister in Jesus’ name, grounded in our roots, enlightened by the Gospel and the Council and relying on Divine Providence, as we “work for a future in which the poor and suffering, the hungry in body and spirit, will know God’s saving love present in them.”

Some 140 years after the Osage Mission school, the Gathering Place in Thoreau, N.M., was established by Sister Angela Bianco SL, RN, along with a group of Navajo residents. Their goal was to promote economic development, education and health care services. They established the Navajo co-op, an artist cooperative that supported Native American arts and crafts, in addition to literacy programs and the Little Mother Program to support expectant and new mothers.

Co-member Jane German was on the board and participated until its closure in 2010. Jane spent 30 years working with the Navajo community in the Thoreau area as a teacher.

Another Loretto Co-member, Sharon Palma, says when she reflects on the numerous years she has spent with the Native American people in New Mexico, what she feels most is great gratitude. Says Sharon, “My life here on the Jemez Indian Pueblo, the Zia Indian Pueblo, and the Navajo Tribal Land has been as friend, school counselor, and facilitating service trips for and with the senior students at Nerinx Hall High School, via Cathy Hartrich. It has been a tremendous honor to live side by side with the people I’ve made friends with, and who have shared their lives with me, a different culture, but not a different race. We are all of the human race! The Indigenous People I’ve lived and worked with these past 30 years are resilient and deeply connected to the earth and their creation spirituality. And they have stretched me spiritually, emotionally, socially, and with love! They’ve brought me to a place of ‘Oneness’ that I had not known before.”

Most of Sharon’s work has been with the Jemez Pueblo people, and Sharon notes she found a Loretto connection there. “Back in the 1940s when some of our Sisters were teaching in Bernalillo, there were some students from the Jemez Pueblo. When commodities were first given out, the Native American people receiving these needed to have a surname. Most at that time did not have surnames, and so several ‘adopted’ the name ‘Loretto.’ As a result, there are many Loretto families now who live on the Jemez Pueblo, and we are now ‘relatives,’ friends certainly! Their surname has stuck and is moving down through the ages.”

Sharon adds that when she and Cathy teamed up, they brought 14 Nerinx seniors at a time for a week of service work on the Jemez Pueblo. The students “mended fences, painted the inside of the elders homes (that were badly in need of paint, from burning wood stoves for many years), bonded with some of the families, especially the elders, who shared their creation stories with the students, and helped plant the Native squash, corn, chili, etc.” Several students, Sharon says, stayed in touch with the people they had bonded with on the Pueblo; “some students brought their parents and grandparents out here to meet their new ‘relatives.’ Several of the students have stayed in touch with the Pueblo people. Cathy brought her students out here during summer and different breaks for several years. It was a real time of sharing and learning between the cultures, and a real meaning of ‘Oneness’ for all.”