Loretto in Taos

Posted on May 10, 2018, by Eleanor Craig SL

The late August numbers of the Taos newspapers in 1913 carried the following, in Spanish and in English:

GOLDEN JUBILEE

The Sisters of Loretto Spend Half a Century in Taos, New Mexico

Early in 1863, Rev. Father Gabriel Usell, the then parish priest of Taos, New Mexico, recognizing the need of a convent and Sisters to instruct the young of Northern New Mexico, petitioned the church authorities to establish a colony of the Sisters of Loretto at that place.

Three Sisters of that Order were started overland from Santa Fe. The superior was Euphrosyne Thompson, and Sister Ignacia Mora and Sister Angelica Ortiz accompanied her.

These three sisters opened a convent in the house now occupied by Don. Santiago Romero, this house having been purchased for them by Father Gabriel with funds derived from the sale of his horse and buggy.

On November 3rd, 1863, a school for girls was opened with an encouraging attendance.

Fifty years of Loretto in Taos! And there would be almost one hundred more years! Who were these Loretto women? What part did they play in Taos history and what was their daily life like? Fifty years had seen a lot of change in the hometown of Kit Carson and Josefa Jaramillo; the culture of the old Spanish Catholics had been slowly giving way to the Anglo culture brought by railroads and the Protestant ranchers. Much of the change can be read between the lines of the Sisters’ record book called The Annals:

October 15, 1863. The Sisters left Santa Fe for Taos, the whole journey of seventy miles being made in carriages over very rough roads, through mountains, and along the Rio Grande. …The Sisters were obliged to walk nearly half the way. In those days such journeys were considered pleasure trips! Railroads were not thought of.

The Sisters’ record book contains day-by-day entries—amusing, interesting, surprising, impressive, quaint, and occasionally disturbing. Taken together, the annals for the first 50 years of Loretto in Taos give a uniquely detailed picture of the work and lives of women of substance, dispelling many of the usual caricatures. These annals are available in the archives of the Loretto Heritage Center on the grounds of the Motherhouse of the Sisters of Loretto in Nerinx, Ky.

The Sisters had been invited to Taos by the local priest, Gabriel Ussel, the appointee of the new French Bishop Jean Baptiste in place of Padre Antonio Jose Martinez, who had lived among and served the people of Taos for decades. Martinez refused to relinquish his large cache of cultural and religious power; he separated himself and many in the Taos community from the bishop’s church rather than comply with Lamy’s project of reforming the Hispanic clergy. The Sisters’ school was to be a bridge between Ussel’s and Martinez’s factions of the Church in Taos. According to the Sisters’ annals, “November 2, 1863. The school opened with a very good number of girls. … At that time there was a schism in the parish, but all parties patronized the Sisters’ school the same.”

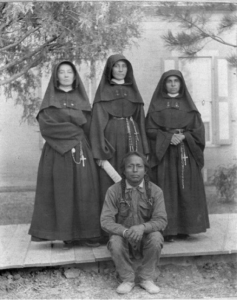

The three Sisters who arrived in October 1863 were a representative mix of Anglo and Hispanic, just like the Loretto Community they had left in Santa Fe, and just like the Taos community they came to teach. These are the three who opened school in the same building that was their convent just two weeks after arriving:

Euphrosyne Thompson (Elizabeth Catherine Thompson, 1839-1908), was 24 when she was sent from Santa Fe with two others in 1863 to establish the school in Taos. Euphrosyne had frontier courage in her blood, being one of a pioneering family that had settled in Maryland in the 1630s and emigrated to Kentucky after the Revolutionary War.

Ignatia Mora (Pilar Mora, 1842-1901), was schooled in her family’s home in Albuquerque, N.M., as a child; she attended Our Lady of Light Academy in Santa Fe for four years of high school, then worked a year with Euphrosyne in the Loretto day school. She entered the Loretto novitiate in Santa Fe in 1859 at the age of 17. She was 21 when she accompanied Euphrosyne and Angelica to Taos in 1863. There she taught art and the sciences until going to Las Cruces, N.M., to take charge. She returned to Taos in 1898 for three years when in her mid-50s. She died in Santa Fe in 1901.

Angelica Ortiz (Petra Ortiz, 1839-1913) was 24 when she was sent to Taos in 1863. She had been one of the earliest students at Our Lady of Light Academy in Santa Fe, and was one of the first to be received into the Loretto novitiate in Santa Fe. She was 16 years old, among the first Hispanic women to join Loretto. She may have worked with Euphrosyne at the day school in Santa Fe from 1858 to 1863. She was with Euphrosyne and Ignatia Mora in Taos for only one year. She circulated from year to year among the Santa Fe academy, and the schools of Las Vegas, N.M., and Mora, serving with Euphrosyne in both Las Vegas and Mora. Angelica died in Santa Fe in the 50th anniversary year of the school she helped establish in Taos.

Loretto Schools in the 1860s were privately owned and operated by the Sisters of Loretto. The Taos school was to be such a private school; it would not be purchased by the church parish until the 1920s. A few of the more than 30 academies established by Loretto between her founding in Kentucky in 1812 and the arrival of Sisters in Taos in 1863 include Our Lady of Light in Santa Fe, 1852; Loretto Academy in Florissant, Mo., and Osage Mission, Kan., both in 1847; St Benedict’s in Louisville, Ky., 1842; Loretto Academy in Marion County, Ky., 1834; Bethlehem Academy, Perry County, Mo., 1823; Gethsemani School in Nelson County, Ky., 1818; Calvary Academy at Holy Mary, Ky., 1816.

In Taos, the founding Sisters’ first housing was provided by the local pastor as an incentive for them to come in 1863. Over the years the Sisters purchased additional acreage, built a two-story adobe building (1882), large enough to house three or four Sisters and as many as 22 boarding students. Two large classrooms held 80 to 100 students each, one for primary grades, the other for intermediate grades. In addition, there was a gathering hall and space for one of the Sisters to teach private music lessons.

Each of the academies was set up to be self-sufficient; tuition and donations received from students’ families and local supporters were the sole sources of income — plus, of course, all the fundraisers, programs, socials and so forth that brought in funds one nickel and dime at a time. When income fell short in a given year in Taos, the Sisters cut back on comforts, delayed needed repairs, took in sewing and washing, took on more private music students, dismissed paid help and took care of even more of the outdoor and indoor chores themselves. Finally, they sought paid positions with the public school system.

Thirty years after the Sisters arrived, they individually signed contracts with the Taos School Board to teach public school classes for the short four or five months of the public school year. In the first year, 1894, one Sister and her classroom was hired for the public school; simultaneously the other Sister and classroom ran “our private school.” In succeeding years two and sometimes even three Sisters would have public contracts, depending on the number of students recruited by the school board. Each Sister taught between 80 and 100 children in ungraded classes. When numbers warranted, the school board rented more space in the Sisters convent and contracted lay teachers. Whenever one or more Sisters were not under contract, they opened the private school to enhance their income with private tuition according to ability to pay.

Shortly after their 50th anniversary in Taos, the Sisters opened high school classes under contract to the school board. ome years the salaries and/or rent were not forthcoming for months. The Sisters’ annals — the account of daily life kept in the convent — record:

1905-06. The School Board refused to employ Sisters in the public school, so the Sisters had to rely on their little private school, so the year was extremely hard for them.

“August 16, 1910. Difficulty about the contracts for the public school, as is usual. They do not want to pay us rent. We shall be glad when that old Lee Witt is out. Ed Espinosa is against us too — a boy who was educated here too; so Mr. Montaner can do very little. Mr. Dwire is still the same kind friend.

“February 26, 1915. We may have to wait some time for our salary as we have been informed that there is no money in the treasury to pay for the month just closed.

From the beginning of teaching for the public school, the Sisters in Taos were targets of disapproval, which gradually hardened into fierce opposition. The Sisters saw great irony in this, since in many parts of the Rocky Mountain west, the Loretto Sisters were the first or among the first to qualify for public school teaching certificates. In Taos the courses for teacher training which were organized by the school board were held at the Sisters’ convent, using the Sisters’ classrooms as demonstration sites. School Superintendent Mr. Montenar said more than once, “The Sisters’ school is the only one worthy of the name and the best teachers in the county are those who had been taught by the Sisters.” Nevertheless, in a school board election in 1912 a majority of citizens voted for the candidate who opposed the Sisters, according to the Sisters’ annals:

April 1, 1912. Such exciting times today. It was the election of a member to the School Board. …There were two candidates: one for the Sisters and the other against us. It was a hot contest; carriages were running all day back and forth, carrying voters, the women voting for the first time in Taos. Many wanted the Sisters to go and vote, even Father was thinking of it. …We did not go and we were delighted, too, that we did not. For the opposing party won. So it is well we were not seen. Many are against us and want us out of the school.

Religion and culture scholar Kathleen Holschner, in her 2012 book “Religious Lessons”, writes that these conflicts culminated in the 1948-51 “Dixon Case,” and resulted in the baring of Sisters in religious garb from public school teaching in New Mexico. Holschner attributes some of the animas against the Sisters to the belief of Protestant Americans that nuns would of necessity force their students into what then was viewed as the anti-democratic mindset of the Roman Church. A closer look at the cultural background of Loretto women teaching public school in Taos suggests they were not likely to behave like their European counterparts.

Euphrosyne Thompson was 19 when she traveled by steam boat and mule train from her Kentucky roots to Santa Fe in 1858. Rosanna Dant (Ellen Dant, 1834-1916), followed Euphrosyne as superior in Taos in 1875, but she came earlier to New Mexico, being one of the original four who traveled from Kentucky to Santa Fe to establish Our Lady of Light Academy in 1852.

Both women were granddaughters of Kentucky’s first settlers, themselves pioneers from Maryland whose ancestors had arrived in the New World six generations earlier, with the waves of Protestant pilgrims. Both Sisters had grown up in the “Catholic Holy Land” of central Kentucky, a community of independent-minded Maryland Catholics imbued with the spirit of the American Revolution, practiced in the resilience and self-reliance of the frontier —- even self-reliance in spiritual matters, for they practiced their Catholicism without benefit of clergy for months and years on end.

Sister Euphrosyne and Rosanna and all the other Loretto women were members of an entirely American religious order which had sprouted in Kentucky soil in 1812, unencumbered by European ties or models of religious life. The earliest school of the Sisters of Loretto had as its first rule, “No Denomination is refused, if willing to observe the Rules of the School – the other Denomination will not be forced on Sunday & Holyday to go to the Chapel & perform our Christian duties, but they must suffer to be friendly; invited in the School they are to be present at every exercise & to behave, if not in a Religious, at least in a civil manner.”

Despite Loretto’s openness to democratic diversity, the public school connection continued to be uneasy, finally coming to an end in the spring of 1928. Our Lady of Guadalupe Parish purchased the property and St. Joseph’s went on as a parochial school with the Sisters of Loretto as teachers until the school closed permanently in 1973. Sisters worked in other capacities in Taos until 1976. In August 1987, Loretto Sisters returned to Taos, contributing another 25 years to the community.