Federal Census Evidence for Loretto Slaveholding, 1820-1860

Posted on November 18, 2020, by Loretto Community

(Editor’s Note: The Loretto Community is working to understand its complicity in systemic racism. We thank the Loretto Heritage Center staff for providing important research about Loretto’s history of slaveholding. We cannot atone and change without knowing the truths of our past.)

By Susanna Pyatt

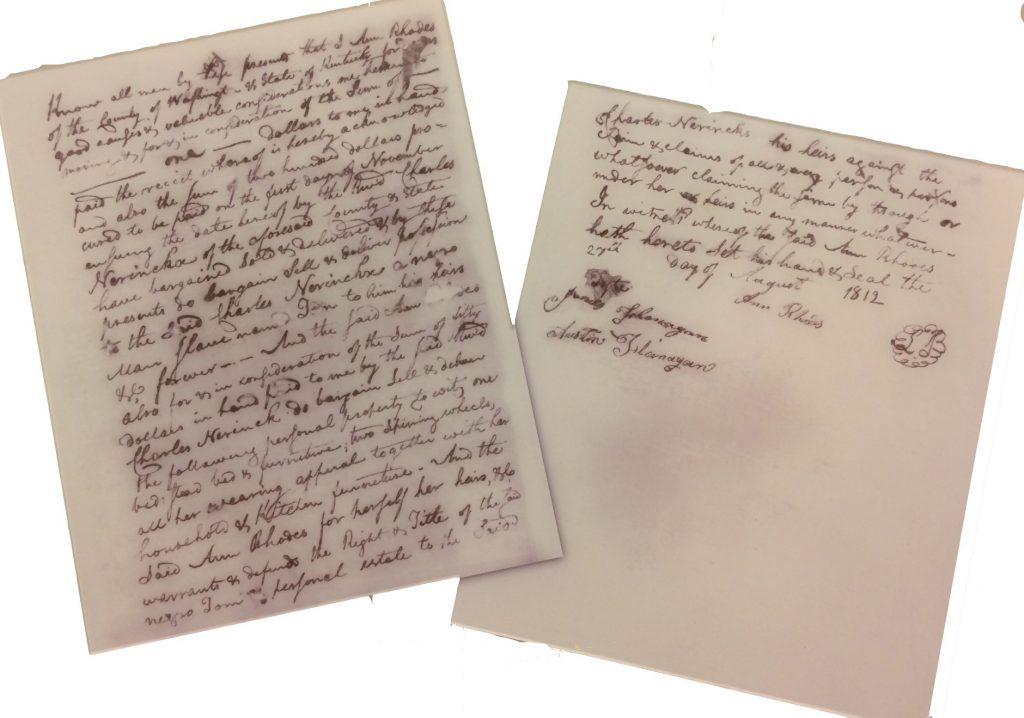

Knowledge that the Sisters of Loretto were slaveholders prior to the Civil War is nothing new. The Loretto Community erected a “Slave Memorial” in 2000. This stone marker, engraved with the names of people of color known to have been involved with Loretto, was placed in the cemetery at the Motherhouse in Nerinx, KY. We have a bill of sale for Tom, an enslaved man, attesting that Mother Ann Rhodes sold Tom to Father Charles Nerinckx for $200 in 1812. Thus slavery was literally part of the foundation of Loretto, providing substantial initial funds for Ann Rhodes and her fellow Sisters to start their congregation. There are some records for enslaved people being purchased by Loretto or brought to the congregation by women joining the order. And we know that for a brief period in the mid-1820s, women of color were accepted into the Loretto community as Oblates, considered members of the congregation but living with different Rules, dress, work, and timeline for professing vows than white Sisters.1

Besides these facts, we know few details about Loretto slaveholding or what life at Loretto houses was like for people of color during the antebellum period. Many historic documents likely burned in the Motherhouse fire of 1858, and records from several other Loretto schools and convents were similarly lost in fires at those institutions or did not make it to the Archives for other reasons. A few references to enslaved people can be found scattered across the existing records.2 When we do find new mentions of the people enslaved by Loretto, it is often by happenstance as we peruse the papers for unrelated information.

So, with spotty records of our own, where else can we look? It turns out that federal census records are a good starting point. There is much they do not tell us – the actual names of enslaved people, for instance – but they can at least provide a more comprehensive view of the scope of Loretto slaveholding, as seen in snapshots taken every ten years.

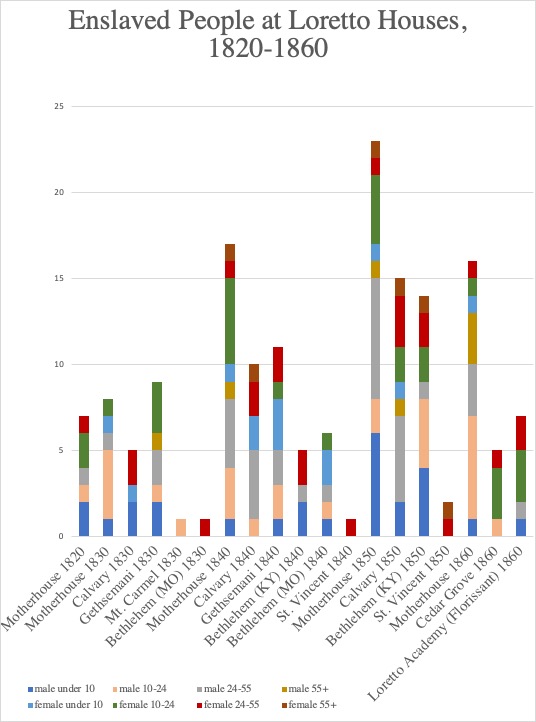

Take the year 1820, to start with. Loretto had been established as a congregation of women religious for eight years. In addition to the Motherhouse (Little Loretto near St. Mary’s, KY), the Sisters had houses nearby at Calvary and Gethsemani. The 1820 census record for “Mother Ann’s Congregation of Nuns” lists 7 enslaved people, 4 men and 3 women. Their presence at the convent raises many questions. Were they all at Loretto solely to provide labor? Were the women part of the trio who became Oblates in 1824?3 Were any them at Little Loretto because part of Father Nerinckx’s advertised vision of the congregation was for it to become “an asylum or shelter for old age, decrepit or useless slaves, and whatever kind of sick or distressed fellow creature may call for their assistance”?4 Unfortunately, we cannot answer these questions based on the census record.5

By 1830, Loretto had expanded still further. Several foundations did not last more than a few years, but when the census was taken, there were schools and convents at the Motherhouse (now relocated to its present site), Calvary, Gethsemani, and Mount Carmel (Breckinridge County)6 in Kentucky, and at Bethlehem (Perry County) in Missouri. There was at least one enslaved person at each of these locations, including enslaved children at the Motherhouse, Calvary, and Gethsemani.

Generally, as Loretto founded schools in Kentucky and Missouri, enslaved people were part of the academy households. As many as 23 enslaved people lived and worked with each foundation of Sisters and students. As one can see from the chart, slaveholding continued through the last census before Emancipation, though, from the records we could find, apparently somewhat diminished between 1850 and 1860. Loretto may have held entire family units under enslavement, as the enslaved people in Loretto households often included young children and sometimes infants.

1860 slave census page for Loretto Academy (Nerinx, KY), showing the age, sex, and color of enslaved individuals. Image courtesy of Ancestry.com.

What happened to all of these enslaved people after the Civil War and Emancipation? The census records do not tell us for sure, but it is clear that most, if not all, of these people did not continue to reside in Loretto households. It is possible that the formerly enslaved people stayed in the vicinity and were hired to work at Loretto places but lived in their own households; however, the census does not give evidence one way or the other for this hypothesis.

What the census does show is a shift in the demographics of live-in laborers. Several of the 1870 and 1880 records for the formerly slaveholding Loretto houses show a couple of house servants – typically teenage girls or young women of color – living at each academy. As for other labor, many of the Kentucky and Missouri houses have multiple adult male laborers, typically white and unmarried, listed with the household. At least in terms of residential labor, Loretto appears to have shifted from primarily enslaved people of color of all ages to primarily young, single women of color and single white men.

The census records give us a better idea of the scope of Loretto slaveholding: they are clear evidence that the Sisters were slaveholders, relied on enslaved labor as they spread their mission of educating (primarily white) children across Kentucky and Missouri, and held both children and adults—possibly families—in bondage. But the census cannot tell us much more about the relationships between Loretto communities and those enslaved within them. It does not tell us how long each enslaved person lived with Loretto, how each person may have been related to other Loretto slaves, or what exactly happened to these people after Emancipation. The census does not even tell us their names. To answer these questions, we must continue to look for other records outside of our Archives that speak to the experiences of people enslaved by Loretto. We intend to invite scholars and other skilled researchers to aid in the search for such records, once it is safe to re-open the Heritage Center to the public, in order to increase understanding of this part of Loretto’s past.

Notes:

1 See O’Daniel, p. 147-151.

2 For examples, see O’Daniel, p. 49-51.

3 Father Nerinckx wrote in a May 1824 letter, “Two days ago, twelve young ladies offered themselves at Loretto for the little veil, amongst them our three blacks, who received nearly all the votes!” (qtd. In Camillus Maes, The Life of Rev. Charles Nerinckx, p. 510).

4 Qtd. In O’Daniel, p. 70.

5 The 1820, 1830, and 1840 censuses list households, giving the names only of household heads and tallying all other members (white, free “colored,” and enslaved) as numbers under general age ranges for each sex. The 1850 and 1860 censuses give more detail, listing each person individually. There are separate censuses for free and enslaved people; the slave schedules generally do not give individuals’ names, only their age, sex, and whether they are “Black” or “Mulatto.”

6 At the end of 1830, Mt. Carmel was moved to St. John, Hardin County, KY, and re-named Bethlehem Academy.

Further reading:

Laura Michele Diener, “O Hail, Mary, Hail: The Long Complicated History of an American Convent,” Numero Cinq (October 10, 2016)

Hannah O’Daniel, Southern Veils: The Sisters of Loretto in Early National Kentucky (MA thesis, University of Louisville, 2017)

Rachel L. Swarns, “The Nuns Who Bought and Sold Human Beings,” New York Times (August 2, 2019)