Teaching: From the Three Rs to the Higher Branches

Posted on August 16, 2018, by Eleanor Craig SL

Two buildings on the grounds of Loretto Motherhouse are in the midst of significant anniversaries. The buildings that today we call “Rhodes Hall” and the “Novitiate/Academy Building” together mark 175 years of young ladies’ education at the Sisters of Loretto Motherhouse in central Kentucky. In later blogs we’ll look at the story of the 1886 Academy Building. But first, the beginnings of Loretto teaching in frontier days.

Late in 1824 the Sisters of Loretto left their place of origin, “Little Loretto,” reluctantly accepting Bishop Flaget’s offer of Reverend Stephen Badin’s abandoned farm in exchange for their original log cabin compound. As many as fifty sisters were displaced, together with the students who boarded with them, and an assortment of widows and enslaved and free women of color who shared the sisters’ lives in some ways. Sisters from the nearby Calvary and Gethsemani houses came to help pack.

In the damp cold of November all these women and girls set out on the country road following wagons carrying their household goods, school and chapel supplies the long twelve miles to Badin’s hilltop near Holy Cross. There they fell to work immediately to reestablish the daily routines of convent and school, creating around Badin’s brick house the nucleus of what today is Loretto Motherhouse.

School was resumed as soon as possible. Mother Isabella Clark, who presided over the displaced settlement, said in memoirs written many years later that from Loretto’s beginning most of the young boarders were orphans. But Loretto wasn’t just educating children. As early as 1814 there had been a steady and increasing number of aspirants to the Loretto Society, many as young as 13 and 14, and all needing to be taught so they in turn could teach others. At Little Loretto when Father Nerinckx began his talks with the words “Oh, Sisters and Scholars,” perhaps he meant both the sister-teachers and the sister-scholars, as well as the children.

There is very little documentation in the Loretto Archives about what the sisters taught; however, we can make some inferences from what is known about other schools in the area at the time. Opportunities for girls were slow in developing in rural Kentucky, but as early as 1807 the Dominican Fathers at St. Rose near Springfield had accepted twenty-two boys as students, six of whom were admitted as novices intending to join the order. All were students in the “College of St. Thomas of Aquin (sic),” not a college in the modern sense but a school which taught “the common branches” of reading, writing, arithmetic, geography and catechism, and which added the “higher branches” as students progressed to languages, literature, science and philosophy-theology.

Mutual influences on the frontier make it quite likely that Loretto also followed this pattern of education, including the practice of teaching the novices with the rest of the students. Some early Sisters of Loretto, like Isabella Clarke and Mary Ann Fenwick, were related to the Dominicans and other priests influential in education. Girls at Loretto were the sisters and cousins of boys at St. Thomas Aquin (sic). By the 1830s Loretto employed St. Mary’s Seminary professors to coach the sisters in teaching some of the “higher branches”.

Just six years after Loretto’s move to Badin’s farm, plans were underway for a new and imposing building to house an “Academy,” a school that would offer both the common and higher branches. In the February 8, 1834 issue of the Bardstown Herald is this notice: “The beautiful building intended for the reception of pupils …will soon be completed. As the expenses incurred for the erection of the new building have been truly great, for they will not fall much short of $6000, I hope from a generous public, to meet with favorable encouragement—(Signed) Miss Josephine Kelly”

The splendid brick Academy, facing ‘Bardstown Road,’ still stands in 2018. Its opening marked Loretto’s participation in an early 1800s phenomenon in education: the gradual transition from home-based and boarding school teaching to “female seminaries.” By the mid-nineteenth century, female seminaries and academies were everywhere, replacing the homelike atmosphere of boarding schools with a more institutional setting.

Large, classical edifices housing dormitory rooms, chapels, dining halls, and classrooms with desks aligned in rows became standard. At Loretto Academy, carvings by Brother Charles Gilbert on the portico of the front (today the back) porch provide the only list we have of the “higher branches” offered at the new Academy: Maps and the use of Globes; Astronomy; Algebra, Geometry and Trigonometry; Physical and Biological Sciences; English Literature; Music on the Harp, Piano, Guitar and vocal Music; Drawing, Painting, and Fine Needlework.

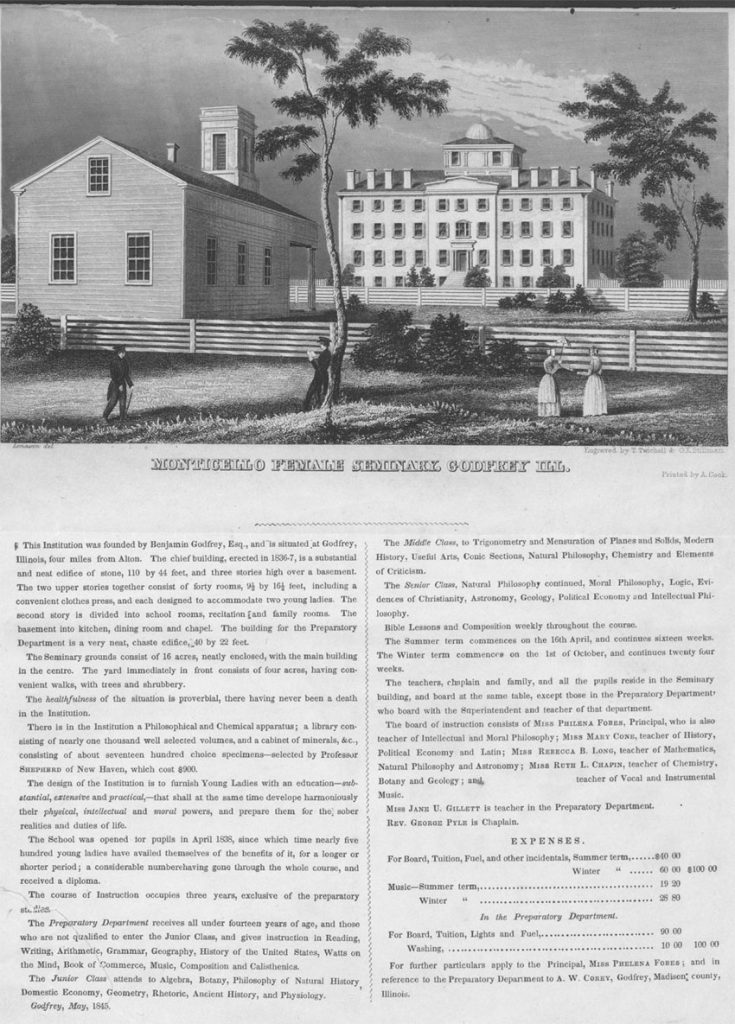

While the Loretto Archives has only a few tantalizing documents, many details about academy life in the 1830s can be explored on line at a charming website of the Clement Library at the University of Michigan. This link http://clements.umich.edu/exhibits/online/womened/Institutions.html includes the story of Monticello Seminary, near St. Louis, which opened in 1836.

Like Loretto Academy in Kentucky, Monticello Seminary was created for girls and young women who would otherwise have little opportunity for education. Benjamin Godfrey, a self-made businessman, was impressed with a mother’s influence on a child’s early development. He endowed and built his seminary to educate the daughters of farmers and shopkeepers.

Reproduced from http://clements.umich.edu/exhibits/online/womened/Institutions.html

Primary & Advanced Studies

Primary studies for women included Reading, Writing, Arithmetic, and Geography and basic sewing stitches, usually in primary schools in the neighborhood. Primary schools were both private and tax supported “district schools.”

For further education, parents sent their children to advanced schools called variously “academies,” “seminaries,” “institutes,” and “colleges.” The central subjects of the female curriculum were composition, rhetoric, the emerging “new” sciences sometimes called “natural philosophy,” algebra, history, moral philosophy, and French. Latin was popularized for women around mid-century. Some advanced female schools specialized in fine needlework, art, and music.

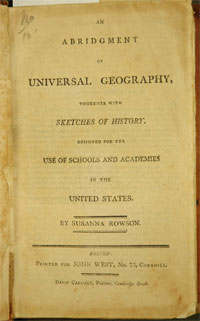

Reproduced from http://clements.umich.edu/exhibits/online/womened/FemaleCurriculum.html

Books used at Loretto Academy in the earliest years included: 1832 edition of Keith on Globes; 1838 edition of Hunt & Noyes’ History of the Revolutions in Europe; Echard’s Roman History, 1696; Gorion’s Wonderful and Most Deplorable History of the Jews, 1662; Tooke’s Pantheon, 1838; Comly’s English Grammar, 1839; Elemens de Politesse, Provost, 1766.