Studying the Sisters of Loretto’s involvement in the Native Boarding School Era

Posted on March 14, 2023, by Loretto Community

Loretto wishes to share with you the research of the congregation’s study of the history of Native Boarding schools operated by the Sisters of Loretto.

Why We Study the Native Boarding School Era

In 2012 the Loretto Community was dismayed to learn of the Doctrine of Discovery, the religious, political and legal justification for colonization and seizure of land not inhabited by Christians. We confronted the history we had ignored and how we had allowed our own ignorance. Loretto repudiated that doctrine in 2012. But repudiating the Doctrine of Discovery is not enough. At the Loretto President’s direction, in cooperation with U.S. Secretary of the Interior Deb Haaland’s Federal Boarding Schools Initiative, we are studying the history of the Native Boarding Schools operated by the Sisters of Loretto during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Loretto President Barbara Nicholas intends that our future actions be informed by what we learn.

View a video of Secretary Haaland’s boarding school initiative announcement below or on the National Native American Boarding School Healing Coalition website.

The Frontier Mentality – Osage Mission School

Mother Bridget Hayden SL is a revered ancestor in the Loretto tradition. She was the second white woman in Indian Territory (now Oklahoma) in 1847. Her students at the Osage Mission School had to move further into Indian Territory so that Kansas could become a state. Resilient leadership helped the Osage Nation endure. Some Osage students remained as boarders when the school became St Ann’s Academy, serving mostly the daughters of settlers.

During this time period, Native youth were expected to adopt European farming practices. “The Plow That Broke the Plains” helps us better understand how European farming practices led to the Dust Bowl, an unfortunate impact of colonization. When we remember Mother Bridget Hayden, we honor the courage and love that motivated her, and we grieve the impacts on her students’ cultural stability and access to land.

Encountering New Cultures – Kentucky to New Mexico

When called to New Mexico Territory in 1852, our Sisters learned Spanish so they could communicate with their students. But when the Bernalillo Boarding School for Indian Girls began with federal funds in 1886, regulations required all instruction to be in English.

How would the Bernalillo experience have been different if Sisters had learned their students’ Native languages?

At least our Sisters stood against the Indian agent** on occasion, insisting that the children be allowed to return home for Christmas and summer vacation. But no amount of kindness — or instruction that had some useful benefit — can erase the harmful effects of separating children from their parents, teaching them a “superior” Euro-Christian culture, and curtailing Native lifeways to free up more land for settlement.

**The Indian agent: A federal employee charged with enforcing federal rules for Indian boarding schools (and other matters involving so-called Indians).

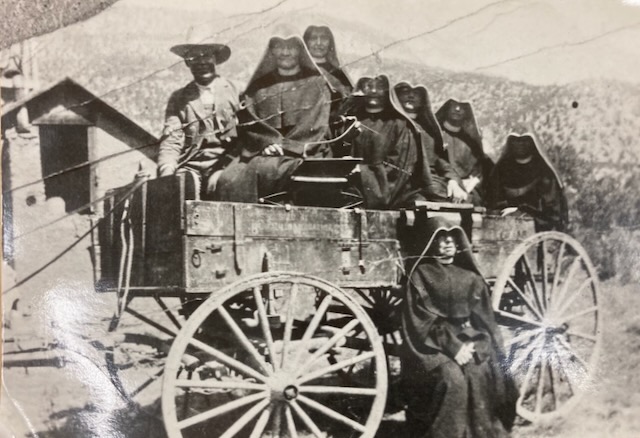

Photo courtesy of Loretto Archives

A Clash of Cultures – Pawhuska

Photo courtesy of Loretto Archives

In Pawhuska, Okla., from 1915 to 1942, the Sisters of Loretto operated the St. Louis School with financial support at different times from the federal government, the philanthropist Katharine Drexel (and the Blessed Sacrament Sisters she founded) and Osage Nation tribal funds from land transfers to the federal government. Twenty-six years after the Oklahoma Land Rush, with the law now requiring tribal lands to be squared off into private ownership to facilitate transfer to settlers, it is no wonder that Native Peoples were severely challenged. A devastating flood greeted the Sisters on arrival, taking out the bridge that connected them to the town. And then the oil boom brought a disorienting materialism to Osage families and a surge of predatory settlers bent on violence.

How did the Sisters respond to all of this? We are grateful for ongoing conversations with the Osage Nation Tribal Historic Preservation Office as we reach for a fuller understanding of our shared history and improved possibilities.

Photo courtesy of Loretto Archives

Photo courtesy of Loretto Archives

Listening to the Land

The written word can provide only an outline of data. When did that school operate; who were the teachers? Did children die there, were they buried there? The gaps in the data hold the questions. Living into the mystery of those questions, we long for healing. How do we reckon with being part of Thomas Jefferson’s plan to reduce Natives’ access to land by assimilating them? We are not the ones of that era who directly caused harm, so we do not respond from personal guilt. Rather, our more complete knowledge allows a level of “response-ability” in light of our values. A Loretto focus group is working with the Nuns & Nones Land Justice Project to imagine ways to respond to the massive loss of access to traditional lands caused, in part, from the boarding school era. Stay tuned as we work our way, step by step, to a better way of relating with Native Peoples and the land.

Photo courtesy of Loretto Archives