The early: Grassroots desegregation at Webster College

Posted on March 1, 2024, by Annie Stevens CoL

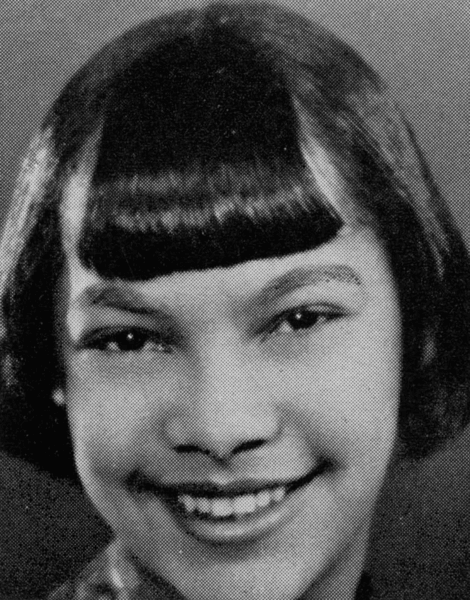

Photo: Missouri Historical Society

As part of my Loretto Roots research in the spring of 2022, I read Professor Shannen Dee Williams’s new book, “Subversive Habits: Black Catholic Nuns in the Long African American Freedom Struggle” (Duke, 2022). She described the African American Oblate Sisters of Providence attending summer classes at Webster College in Saint Louis in 1940-41, which was before the first unsuccessful attempt to desegregate in 1943, or the full archdiocesan desegregation in 1947. Searching archival newspapers, I discovered that not only were African American sisters studying alongside white students in summer school prior to World War II, but a young African American named Vada Lee Easter had been studying music at Webster as early as 1936.

How did this history remain hidden in plain sight? I reviewed the cultural history of Catholics in Saint Louis, historically divided into dozens of ethnic parishes, only one of which — Saint Elizabeth — originally served the Black population. In 1882, Oblate Sisters of Providence (OSP) came to teach at St. Elizabeth’s and later founded Saint Rita’s Academy in 1912. By the 1920s, all teachers became subject to a new Missouri law requiring state certification, leading the OSPs to take Saturday or summer classes at Saint Louis University (1925) and its corporate colleges for women, including Maryville (1938) and Webster (1940).

But who was Vada Lee Easter? I first found her name in a July 1940 news article describing Webster summer school activities, including a music composition contest in which Easter won second prize. Described as a Webster “special music student since 1936,” Easter was also identified by race and photo in published reviews of her piano concert at the Municipal Auditorium in February 1940. Her mother, Mrs. Benne Parks Easter, conducted a music school in the Ville neighborhood of Saint Louis and knew Webster had an excellent music program. Like all good teachers, Sister Adaline Gemoets SL, chair of the Webster Conservatory of Music, recognized a gifted student and wanted to foster that talent. A copy of Easter’s transcript shows she was enrolled at Webster for two years following her graduation from Sumner High School in 1938, then transferred as a junior to Fisk University in Nashville, Tenn., in the fall of 1940. She went on to earn a master’s and doctorate in fine arts, then served as professor and dean at Howard University in Washington, D.C.

Given the presence of these African American students enrolled in education and music classes prior to World War II, it was a shock to Webster and Loretto when Cardinal John J. Glennon did not support the decision by the college to accept another African American student, Mary Aloyse Foster, in 1943. It would take four more years and a new archbishop, Joseph Ritter, until official policy changed to desegregate all Catholic schools.

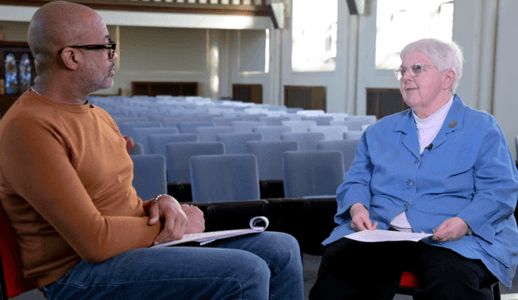

Drawing on this research, I participated on a panel, “Empowering Truths: Navigating and Redefining Black History Education and Institutional Accountability,” at the Webster DEI Conference on Feb. 27, 2024.

Photo: courtesy Annie Stevens