Unraveling the Background of Victoria Whitehair’s Sampler

Posted on June 6, 2019, by Loretto Community

By Susanna Pyatt

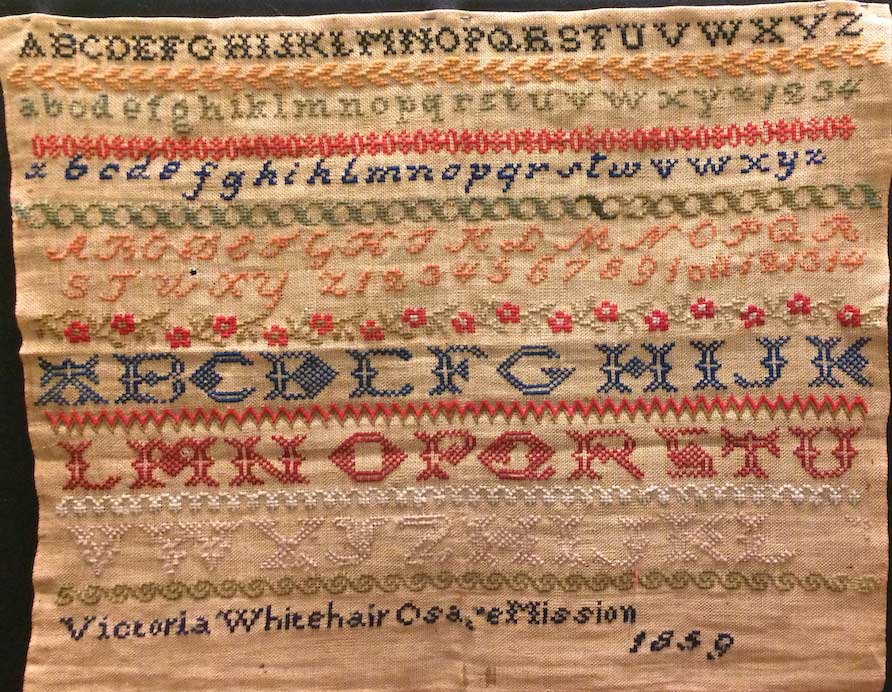

One of my favorite objects in the Loretto Heritage Center collections is an embroidery sampler signed “Victoria Whitehair, Osage Mission, 1859.” Victoria stitched the English alphabet five times in different styles on a linen background, interspersing her lines with decorative patterns. She joined other female students across Europe and America in creating a common schoolgirl art that showcased her education and her needlework abilities. What makes Victoria’s sampler especially notable is that Victoria was an Osage Indian, and few samplers have survived from Native American mission schools.

Next to nothing is known about Victoria Whitehair herself. “Victoria” may not have even been her given name. In the 19th century, Native American children were often assigned English names if they attended school; at Protestant missions, these names were often those of school benefactors.1 “Whitehair” is the Anglicized form of the name “Pawhuska” – the name of several 19th-century Osage chiefs, though I could not find a “Victoria Whitehair” of the right age in their published genealogies. The one historical mention of Victoria Whitehair is found in the 1857 Report of the Commissioner of Indian Affairs. In a list of children attending the Osage Manual Labor School, “H.C. Victoria Whitehair” is described as a 10-year-old who entered the school in 1852. After seven years of schooling, then, she created her sampler around age 12.

The Osage Manual Labor School was founded in 1847 in present-day Neosho County, Kansas. Jesuits under the lead of Father John Schoenmakers began a boys’ school for the Osages, as an experiment in “civilizing” and providing a Euro-American education for the children of a tribe considered by the missionaries and U.S. Indian agents to have “wild” and “savage” customs. The Jesuits were joined later in 1847 by four Sisters of Loretto who had been recruited by Fr. Schoenmakers to open a girls’ school. The two schools grew in number of pupils each year, admitting Quapaw children as well, until the mid-1860s. After the Civil War and the removal of the Osages to Indian Territory, the number of Indigenous students quickly dwindled. The schools became St. Francis Institution and St. Ann’s Academy, and the town of Osage Mission was eventually renamed St. Paul. The Sisters of Loretto left St. Paul after St. Ann’s Academy burned in 1895.

What would Victoria’s experience at Osage Mission have been like? While there are few surviving records from students, a picture of the school can be pieced together from annual reports and other accounts. Subjects taught at the girls’ school included reading, writing, spelling, arithmetic, geography, Christian doctrine, sewing, knitting, lacemaking, embroidery, painting, drawing, music, and gardening. The students also did domestic work at the Mission, including making clothing for each other and helping the Sisters in the kitchen and dairy. The purpose of instruction at Osage Mission was not only to provide a standard Euro-American education for the students, but also to acculturate them to the domestic life and production systems of Western society. Early annual reports of the schools recorded great success in teaching these subjects and skills to the Native American children.

Though the mission was successful in attracting Osage and Quapaw students, school leaders struggled to receive adequate funding and resources from their government contract. Some years, droughts and crop failures left teachers and students with little food. Annual reports to the Commissioner of Indian Affairs also repeatedly requested money to repair and add on to ill-built, overcrowded, uncomfortable buildings that served as both classrooms and lodgings. By 1859 – the year Victoria stitched her sampler – the girls’ school was pushing its capacity with 60 Osage and 13 Quapaw students overseen by 11 Sisters of Loretto. The next year, Fr. Schoenmakers credited illness among the students as due partially to overcrowded and poorly ventilated buildings.

The schools also suffered along with the Osage as the tribe faced multiple devastating epidemics in the 1850s. Fr. Schoenmakers estimated that at least 1000 Osage children and youth died of measles, typhoid, and whooping cough in the spring of 1852. Parents of students at Osage Mission had the difficult decision of bringing sick children home or leaving them at the school, and the choice by some parents to use traditional healing practices put them at odds with the Catholic teachers. Though 25 of the 32 female students at Osage Mission fell ill in the 1852 epidemics, only one died. Given her date of entry, Victoria may have been among the pupils who survived the epidemics at the Mission.

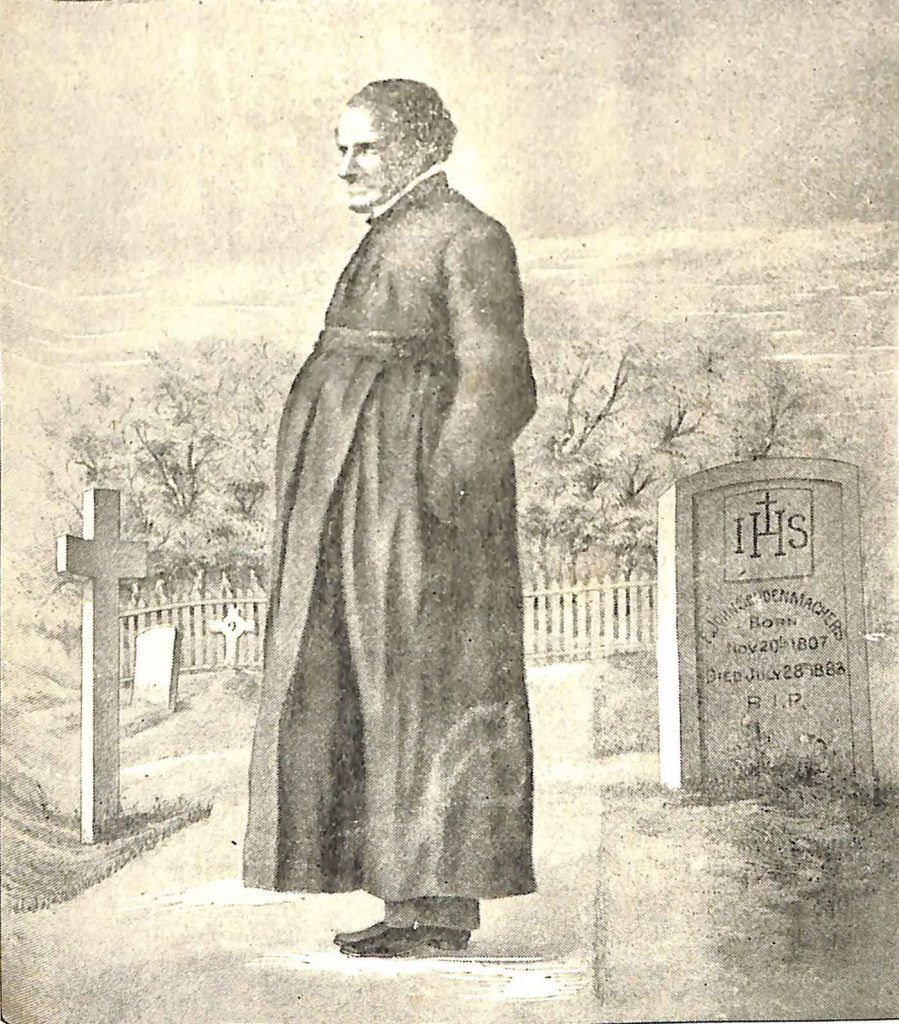

Fr. John Schoenmakers, SJ, and Sr. Bridget Hayden, SL, two of the head Religious at the Osage Mission.

Cultural clashes and misunderstandings between the Osages and the Euro-American Catholics were also an issue. The Osages had requested a mission specifically from the “Black Robes” (Jesuits), but by 1854, Fr. Schoenmakers complained that attendance from most students was inconsistent. Even as students made advances in their Mission education, they were often called back home – sometimes so their skills in English and other areas could be made useful – and returned to traditional lifestyles. For students who graduated from the schools, little encouragement was available from other Osages or from the United States government to continue “civilized” lifestyles. Additionally, tensions between different factions of the Osage people affected the continuation of newly learned habits. Reports to the Commissioner of Indian Affairs complained that while half-blood Osages were open to adopting agriculture and Euro-American lifestyles, full-blood Osages deliberately stymied such changes by destroying fences and killing livestock.

From the Jesuit perspective, the relationship between the Sisters of Loretto and their students was positive, and the girls’ school ultimately had a lasting impact on the Osages. Fr. Schoenmakers reported in 1856, “Seldom heretofore have I seen both teachers and pupils so generally satisfied and affectionate to each other.”2 Writing in 1890, Fr. Paul M. Ponziglione, SJ, credited the education provided by the Sisters as “producing its fruits, in the intelligence, good manners, cleanliness, and religious spirit, which this very day can be noticed in the many Osages [sic] half-breed Indians at the different nice settlements…in the Indian territory.”3

But we have only one side of the story. Victoria’s sampler gives evidence only of her education; it does not say how she felt about her experience as the Sisters of Loretto sought to “civilize” her and other young Native American girls. Despite the primitive and overcrowded conditions at the school, Victoria’s family must have valued the opportunities available there, sending their young daughter to the mission for at least seven years. In a time of great turmoil for the Osages as they survived epidemics, negotiated community tensions, and were forced to migrate from their homes, what did Victoria take away from her time at Osage Mission?

Notes

1 A second surviving sampler from the school, marked “Osage Mission, Souvenir,” may have been created to help raise funds and garner attention for the mission.

2 John Schoenmakers, Osage Manual Labor School, August 28, 1856, in Report of the Commissioner of Indian Affairs (A.O.P. Nicholson, 1857), p135.

3 Paul M. Ponziglione, letter to John R. Brunt, January 28, 1890, in W.W. Graves, Life and Letters of Fathers Ponziglione, Schoenmakers and Other Early Jesuits at Osage Mission (St. Paul, KS: W.W. Graves, 1916), p287.

Sources and Further Reading

Lynne Anderson, “Samplers, Sewing and Star Quilts: Changing Federal Policies Impact Native American Education and Assimilation.” Textile Society of America Symposium, Washington, DC, September 19-22, 2012. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1655&context=tsaconf.

Annual Reports of the Commissioner of Indian Affairs, 1848-1875. http://digicoll.library.wisc.edu/cgi-bin/History/History-idx?type=browse&scope=HISTORY.COMMREP.

A Catholic Mission website, http://www.acatholicmission.org/.

Mary Paul Fitzgerald, SCL, Beacon on the Plains. Leavenworth, KS: Saint Mary College (1939).

W.W. Graves, Life and Letters of Fathers Ponziglione, Schoenmakers and Other Early Jesuits at Osage Mission. St. Paul, KS: W.W. Graves (1916).

W.W. Graves, Annals of Osage Mission. St. Paul, KS: W.W. Graves (1935).