Keeping hope alive in Pakistan

Posted on April 1, 2024, by Loretto Community

By Nasreen Daniel and Maribah

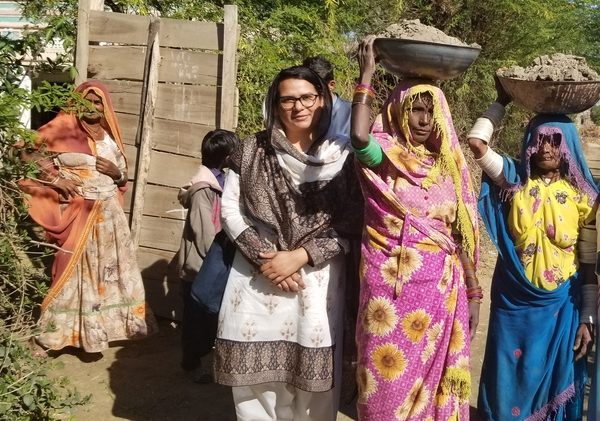

Photo courtesy of Nasreen Daniel

Nasreen writes:

Pakistan has 2.3 million people, or around one percent of the population, working in conditions it labels modern slavery. The most common form of modern slavery is bonded labor. People get trapped when a worker — usually an adult male — takes a loan or salary advance known as peshgi from an employer, labor contractor or landlord. The debtor is obliged to work for that person for reduced wages until the debt is repaid. This typical model of debt bondage covers a wide range of situations, from relatively less severe and short-term to more severe and longer-term. Bonded labor often extends to family members.

Women may be forced to work for little or no wages to repay the debts incurred by their spouses or male family members. The labor of children may be pledged to repay loans taken by parents. Inherited debt can result in bondage that is passed down from generation to generation. Since no written contract usually exists and most workers come from underprivileged social groups with no access to legal counsel, bonded laborers are vulnerable to all forms of exploitation.

In 1995, I was in Sindh when the then-bishop of Hyderabad, Joseph Coutts, with the help of the Human Rights Commission of Pakistan, released about 40 families from bonded labor. He had a piece of land that he gave to the people to build homes and start new lives. Now the Columban and Spiritan missionaries are continuing the same mission, taking a few people at a time and buying land for them to live on and earn a living.

Recently, I took the group of young sisters (including Maribah) from various congregations whom I teach in Lahore to Sindh to witness the lives of these underprivileged people. We named our trip a pilgrimage, and it was a real pilgrimage because all the participants were touched by what they witnessed.

Father Tomas King, an Irish Columban, has been serving more than 25 years in the area. He said that there are many reasons why the Parkari Kohli tribal people feel consigned to the fringe of society. Their ancestors were among the untouchables, at the very bottom of the Hindu caste system throughout a four-thousand-year span of history. The weight of such oppression still lies heavy on their hearts. While their conversion to Christianity a century or so ago helped to provide them with a sense of dignity, major political and demographic changes in the aftermath of World War II left them a tiny religious minority within the newly-created, predominantly Muslim country of Pakistan. Father Tomas believes that the dire situation of tribal people is due to corruption, violence and limited access to education. He also shared that one of every 14 children dies before the age of one.

Photo courtesy of Nasreen Daniel

Maribah writes:

The life of the people in Sindh, a province in Pakistan, is deeply intertwined with its rich culture, traditions and societal norms. One aspect that often garners attention is the practice of early marriage, particularly concerning young girls. Reflecting on this phenomenon unveils a complex interplay of cultural, economic and social factors.

Recently I went to Sindh with Sister Nasreen, where I found a whole new world. I felt I was visiting our distant ancestors, living their lives without electricity, running water (they fetch water from some miles away) and other basic needs.

Even though they are poor, they are rich in hospitality and love. They are so welcoming, offering whatever they have to visitors. The spirit of gratitude in the people is remarkable. They are joyful and happy with whatever they have. They never complain of what they do not have but are thankful for what they do have.

Photo courtesy of Nasreen Daniel

We were invited to the engagement ceremony for a girl who was only 13. The tribal people marry their girls young so they don’t have to feed them and take care of their other needs. At the same time, it is a protective measure, shielding them from societal stigmas of losing family honor if the girl runs away with someone. I was surprised to see that the in-laws put a thick silver ankle bracelet on the foot of the girl during the engagement ceremony; she will get the second when she is married off. This serves as a reminder that she belongs to someone.

We were seated on the handwoven beds covered with beautiful bed covers called ralli which have vibrant colors and a smooth texture. The women of the family sat on the ground. We asked the ladies many times to sit with us, but they said women always sit on the floor. It is their ritual that women remain on the ground as the guests sit on the bed. Even the grandmother, who was the oldest in the house, sat on the ground.

In conclusion:

Reflecting on the life of tribal people and the efforts of the missionaries who are serving tirelessly in such difficult conditions, one can thank them for making a difference in the lives of those who are not a priority for the government. They are building two-room schools in the area so the children can start learning, and they also are teaching trades to those who are interested. The hope is seen already: Twenty years ago, the religious sisters and fathers taught the little children, and now the teachers are hired from within the tribal community. This was a sacred experience for Maribah in the time of Lent. To see Jesus’ suffering face has made this Lent more meaningful for those who visited the tribal area.

Photo courtesy of Nasreen Daniel

Photo courtesy of Nasreen Daniel