Smuggling Mother Mary Out of China

Posted on March 5, 2021, by Susanna Pyatt

Placed in the bottom of a display case in the Heritage Center museum is a “vexillum” or standard, a marble base and orb from which extends a metal pole with an image of the Miraculous Medal (representing the Immaculate Conception) and a sign inscribed “Legio Mariae.” It is topped by a metal dove with outstretched wings, which represents the Holy Spirit. This standard was once used by a Loretto unit of the Legion of Mary, a lay organization founded in Ireland in 1921 whose members serve God, under the banner of Mary, by encouraging others in their Catholic faith.

While the Legion of Mary is still a large and active organization today, the story of this particular vexillum goes back to Loretto’s work in China in the twentieth century. A Legion of Mary group was formed at Loretto’s school in Shanghai in 1948 and quickly grew to include at least two different units, called “praesidia.” But this Catholic activity would prove dangerous as the Communist Army took control of China, such that by November 1952, when the last of the Sisters of Loretto left Shanghai, they had to smuggle the standard out of the country!

In 1948, the Shanghai Lorettines may have been feeling optimistic about their mission. Living conditions in Shanghai had improved substantially since the end of World War II. After over a decade of moving between rented and borrowed homes, the Sisters had finally been able to purchase a suitable permanent location for their girls’ school. Enrollment was strong, the school was already expanding and improving its campus, and the Catholic students were active in sodalities and other lay groups. Father Joseph Seng introduced the sixth-grade Loretto students to the Legion of Mary, and they enthusiastically joined, with a focus on visiting hospital patients and bringing non-practicing Catholics back into the Church.1

But at the same time, trouble was on the horizon. By the end of 1948, Sisters from other Catholic orders were beginning to leave China, worried about the growing power of the Communist Party. Several former Loretto students and their families also evacuated. In Shanghai – an international commercial center for the country – most of the Sisters of Loretto felt relatively safe. Several of the Sisters applied for exit visas, but only one chose to actually leave the country at that time.2

Even as the Communist Party took control of Shanghai in May 1949 and put pressure on foreigners and the Catholic Church, the Loretto school continued and the Legion of Mary grew. Loretto eventually had enough Legion members to form both Junior and Senior praesidia; these were among about 1000 Legion praesidia active in China in 1951.3 Loretto’s Junior group learned to mend and re-bind books in 1950, using their skills to open a lending library.4 According to a spiritual director of the Senior group, the older students had assignments of “hospital visitation, teaching catechism, and study of the Handbook and apologetics. They taught Catholic children who were not going to Catholic schools, and prepared some of them for First Communion…They were responsible for a good number of adult conversions…Many of them joined parish Praesidia after leaving school, and continued to be good, active Legionaries in Shanghai or Hongkong.”5 The Legion of Mary became particularly important to the Shanghai Catholic Church leaders as schools were nationalized and Communist doctrines became required teaching, because the Legion was a way to gather and support young Catholics.6

This strong influence of the Legion of Mary did not sit well with Communist officials. According to historian Paul Mariani, while the Communist Party in China claimed to permit freedom of religious belief and practice, there were foundational aspects of the Catholic Church that led the Communist Party to seek to break the Church’s power in China. The imperialist basis of a religion brought to China by foreign missionaries was one issue. Even more importantly, the absolute dedication to the Church that was advocated by Catholic leaders was at odds with the absolute dedication to the state required by the Communist Party.

In 1951, the Communist Party began to crack down on the Catholic Church in China. The Legion of Mary, as a large and influential lay organization with many active student members, was labeled a “reactionary” group and became a particular target. The two clergymen who led the Shanghai Legion, Fathers Aedan McGrath and Joseph Seng, SSC, were arrested in September 1951. Students were pressured to register with the Communist Party as members of the Legion of Mary and to turn in the names of other members.

Legion members in Shanghai decided to avoid registering, viewing registration as a compromise with the Communist Party that agreed to the label of “reactionary group” when they were actually a devotional group.8 When Catholics did release names of Legionaries, they listed only those who were already publicly known or who had left the country. The Legion was outlawed in Shanghai on October 8, 1951, raising the risk of persecution for members who refused to register.9 Many Legion youth prepared “jail bags” in case they were arrested or summoned to the police station for questioning.10 They were increasingly pressured by officials and police to adhere to the Communist Party and register, and by some of their own parents to register in order to avoid further reprisals.11

Still, most Legion members chose not to register. A group of fifty youth even went so far as to sign a letter in blood for Bishop Ignatius Kung Pin-Mei that affirmed their dedication to the Legion in the face of persecution.12 Stymied, the Communist government relented for the time being. In 1952, the Legion in Shanghai decided to officially disband. Its members could continue the same work and religious commitments in catechism groups, which garnered less attention from officials and would be more difficult to target when persecution resumed.13

In 1952, with increased pressure from Communist policies and dwindling enrollment numbers, the last two Sisters of Loretto in Shanghai closed their school and returned to the United States. They brought the vexillum with them; a later article tells the interesting story in brief. Sister Maureen O’Connell, who had been the first Legion of Mary moderator at Loretto’s Shanghai school, destroyed the two other Loretto praesidia standards but decided to try to smuggle the third vexillum out of the country. Other Legion materials, such as a statue and handbooks, were confiscated or destroyed by customs officials as the final missionary Sisters of Loretto left. However, the officials missed three Legion banners and a vexillum from the Columban Fathers’ Legion unit. They also did not catch the remaining Loretto vexillum, which Sr. Maureen dismantled and declared a paperweight in order to avoid suspicion.

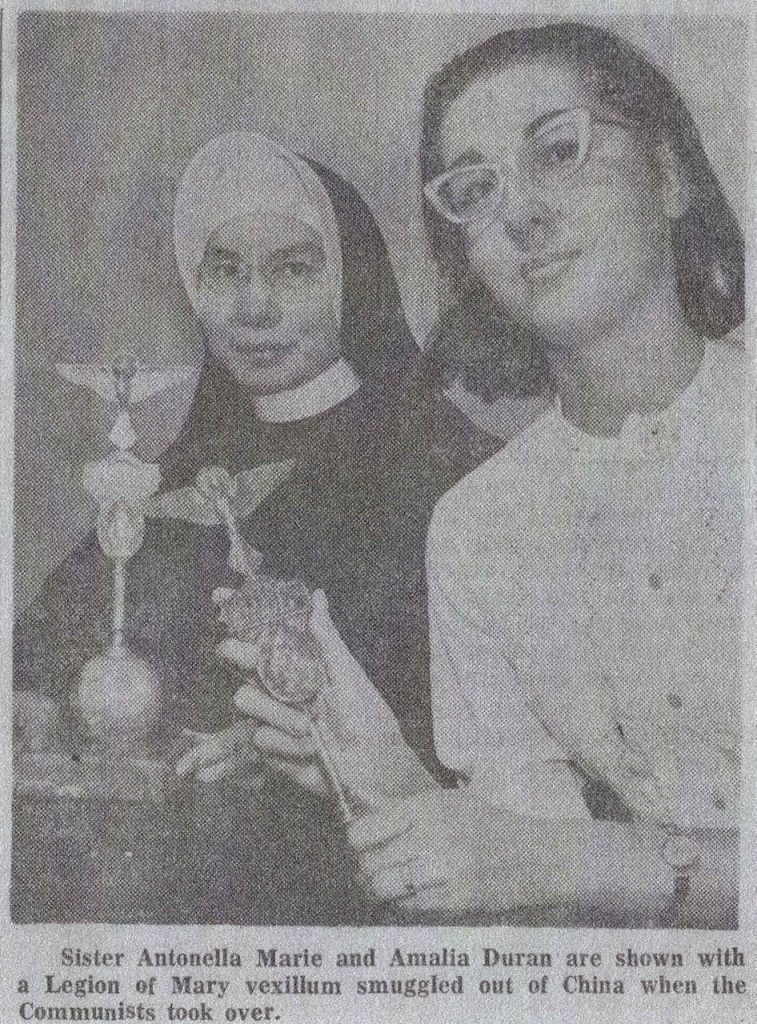

Once safely in the United States, the smuggled vexillum was reassembled. Eventually it went to Loretto Heights College, to be used in a unit headed by Sr. Antonella Marie Gutterres (one of the Sisters who had been exiled from China) and student Amalia Duran (who had left Communist Cuba). The rest of the object’s story is unknown to us, other than it came back to the Motherhouse and was placed in the Heritage Center, where it remains today. Here it serves as a reminder of the persecution faced by Shanghai Catholics in the 1950s as well as a testament to the faith and zeal of young Loretto students, among many others, devoted to Mother Mary as they sought to care for their fellow Catholics in China.

Notes

1 Patricia Jean Manion, SL, Venture Into the Unknown: Loretto in China 1923-1998 (Independent Publishing Corporation, 2006), p. 271.

2 Manion p. 270-271; in order for the Sister returning to the United States to have a traveling companion, a second Sister was told to return also.

3 Antonella Marie Gutterres, SL, Lorettine Education in China, 1923-1952 (United Publishing Center, 1961), p. 108.

4 Manion p. 297; Gutterres p. 109.

5 Rev. Luke Lynch, SSC, qtd. in Gutterres p. 109.

6 Paul P. Mariani, Church Militant: Bishop Kung and Catholic Resistance in Communist Shanghai (Harvard University Press, 2011), p. 46-47.

7 See Gutterres p. 109-110.

8 Mariani p. 79.

9 Mariani p. 82-83.

10 Gutterres p. 111-112; Mariani p. 84-85.

11 Mariani p. 85-86.

12 Mariani p. 87.

13 Mariani p. 95.