A life lived for the sake of the other

Posted on December 8, 2021, by Christina Manweller

Photo courtesy of Loretto Archives

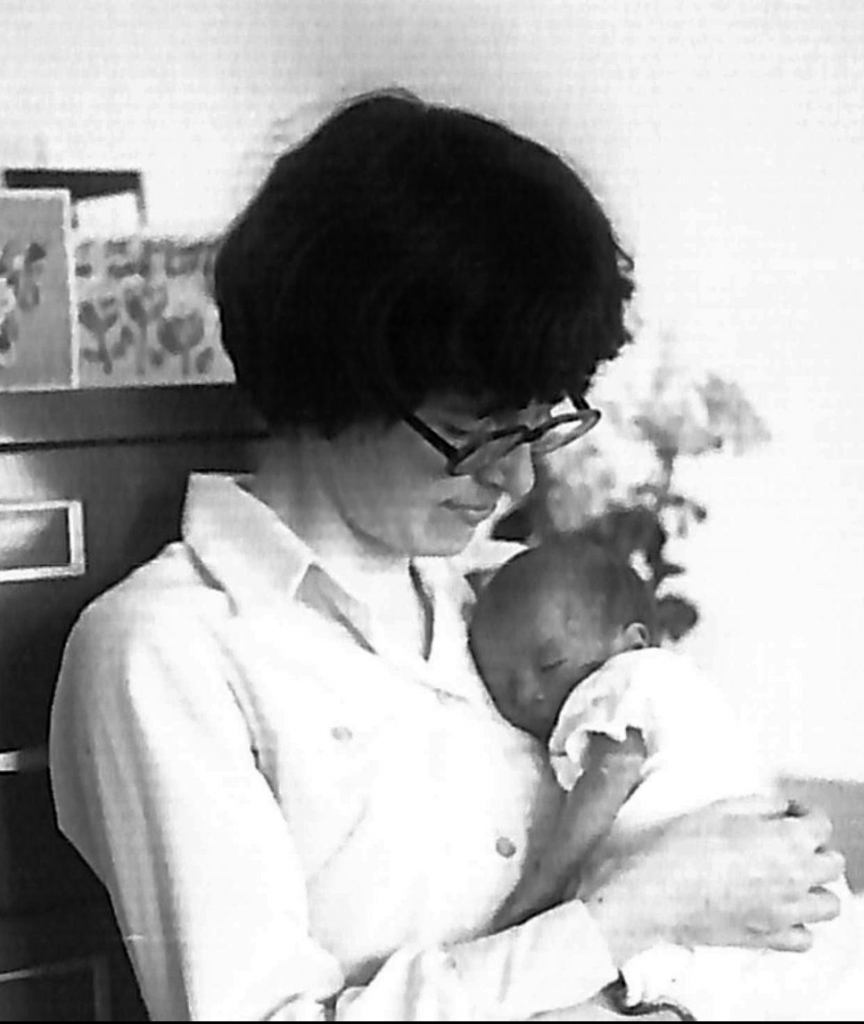

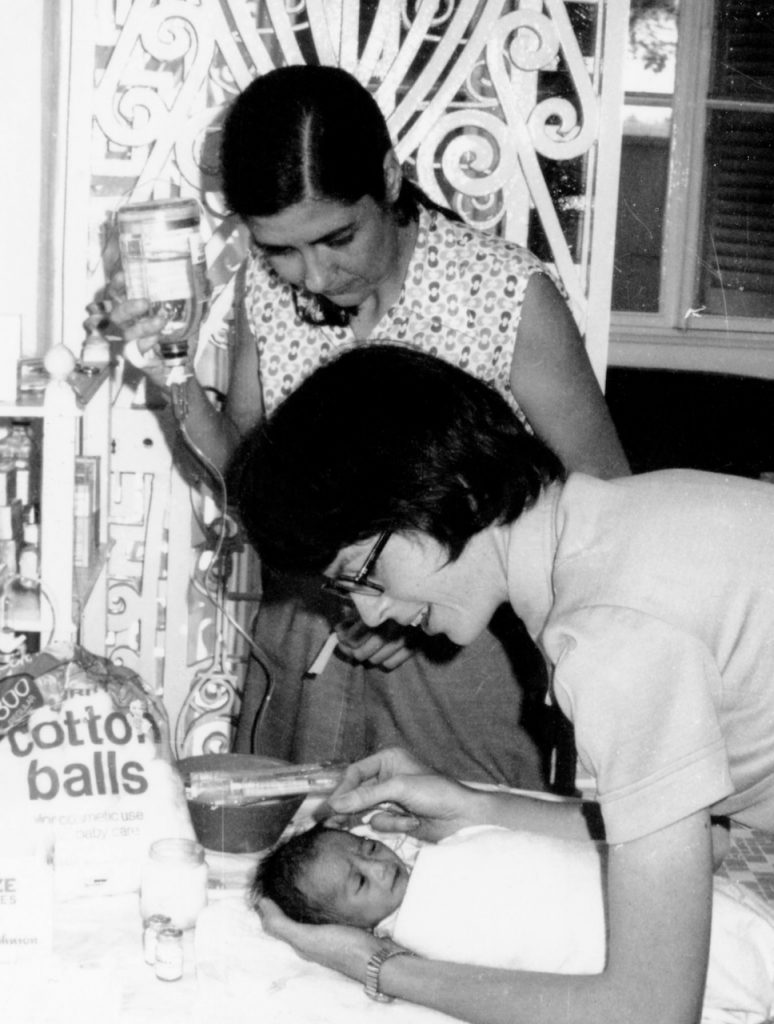

In May 1973, 28-year-old Susan Carol McDonald SL arrived in Vietnam to work with Rosemary Taylor, an Australian nurse who had been caring for orphans and arranging for their adoptions since 1968. Susan, a registered nurse, was asked to take over New Haven Nursery.

TV reports had not prepared her for the stark poverty on the ground — she described seeing people living along the Saigon River which was used as a sewer — but from the beginning she loved her often heartbreaking, often life-saving, work. The newborns arrived one after the next in precarious health, frequently premature and very low-weight. Epidemics struck the orphanages mercilessly. Birth defects and disease were widespread — diseases that a young woman hailing from Colorado had never seen. Children arrived with, or came down with, polio, typhoid, cholera, diphtheria, pneumonia, tuberculosis, meningitis, measles ….

Susan’s skill and determination were invaluable in the face of daunting odds. She was known to manage the miraculous, often nursing to health a child who had not been expected to live. In spite of the love and hard work she poured out, however, many of her charges died.

Photo courtesy of Loretto Archives

The goal was to get orphaned infants and children healthy enough to travel and safely out of the country, all while contending with wartime conditions. In addition to disease, rats, bacteria-ridden water, shortages of supplies and medicine, there were war-related travel snags, to and from the adoptive countries and within Vietnam (Susan routinely took on the fraught task of driving out to provincial orphanages where she picked up orphans and delivered supplies and medicine); there were relentless bureaucratic roadblocks, judges and officials to deal with … piles of paperwork needing officials’ signatures — officials who came and went one after the next.

Susan’s life was a whirl of massive responsibility, of ministering to babies, sleepless nights. She loved it.

Just before the war ended came the most shocking experience of her life, as she later said. On April 4, 1975 the phone rang: Children who had been loaded on a military cargo plane were being brought in wounded. Susan and Rosemary rushed to the hospital where sirens blared and myriad vehicles carried in children and adults. The plane had crashed into a rice paddy shortly after takeoff.

I have dreams about the C-5A crash. In one a friend comes to me and says, “The plane crashed and the children were on it.” Then I am at the crash site. I run toward the plane. Little pieces of paper are flying all over in the air. The air around the plane is filled with these little pieces of paper — like snowflakes. So before I get to the plane I pick one of the pieces of paper out of the air. And on it is a picture of a child. Then in the dream I turn to the others at the crash site; I shout to them, “It’s all right! There weren’t any children on the plane. There were just pictures. Just pictures of children.”

Susan Carol McDonald SL

Volunteers Susan had worked with had died. Children she’d nursed were gone. About half of the passengers on the plane had perished. Over the next days, touring the hospital in a state of shock, she found survivors from her orphanage. If they were well enough to travel, she’d get them on a flight.

By the end of that first week in April the situation was critical; it was clear war’s end was imminent. In the weeks following the crash, over 2,500 children were evacuated. Susan stayed through the month, working to arrange flights, caring for children and attending urgent meetings at the U.S. embassy. She departed on a cargo plane on April 26 with about 200 orphans and 14 adults, including Ruth Routten CoL, who had arrived to assist the evacuation. Susan sat on the floor in the back caring for infants traveling two-to-a-box.

Rosemary and two volunteers stayed a few days longer to close up the orphanages. On April 30, the day Saigon fell to the North Vietnamese army, they were lifted out in a helicopter from the U.S. embassy roof.

Susan was passionate about her work in Vietnam. Relationships she made stayed with her; she was in close contact with adoptees and their families for the rest of her life, frequently playing host in her home and escorting groups to Vietnam.

After the war, Susan worked in Bangladesh, Haiti and rural Kentucky, among other locations. She died in Sept. 2020. Her Vietnam adoptee files and information are at the Loretto Archives, Loretto Motherhouse, Nerinx, Ky.

Photo courtesy of Mary Louise Denny SL