MY EXPERIENCES AS A PROTESTER

Posted on August 18, 2020, by Eleanor Craig SL

I am a white female who grew up in a St. Louis suburb featured in the CBS documentary “16 in Webster Groves” (1966), a critique of the insular life of suburban kids that is still used in sociology classes and reviled by the present upper-middle class residents of Webster.

My parents were educated middle class natives of St. Louis; my mother’s family had contributed to the development of Webster Groves in the 1880s. I knew as a child that I “belonged” in Webster Groves where my grandparents, aunts and uncles also lived. Yet, something gave me a different perspective on that belonging. Perhaps it was that our family finances, which were tenuous, gave me a sense of being marginal.

Certainly it was also that I attended the Catholic parochial school, and the Sisters of Loretto high school, Nerinx Hall, and Loretto’s women’s college, also called Webster. I think my schooling, especially with Loretto, gave me the attitudes of an independent thinker and prepared me to be a protester.

Of course, I was very much like the Loretto women themselves: daughters of a Catholic minority, educated in the mid-20th century as intellectual liberals, purposefully prepared to be leaders in Catholic education. Sister Jacqueline Grennan was my English teacher at Nerinx Hall for three years, a woman equally proud of her farm roots in Illinois and her professional work for President John Kennedy’s administration.

Even in grade school I experienced some of the attractions of speaking out. I won an essay contest and was invited to read the piece I wrote on “Self-reliance” to an evening audience at the public library. As soon as I stepped up to the podium and looked out at the (very small) audience, I knew this was something I could do! Years later, I was equally drawn to speaking out at shareholder meetings and before TV cameras.

Direct action protesting, however, is different from public speaking. It’s a put your body on the line proposition. While a sophomore at Nerinx Hall, I saw my first opportunity—really, the first need—for direct action, but it came to naught. Our class officers went out to lunch and came back irate because the restaurant wouldn’t serve the class secretary because she was African American. Amazingly (but remember how insular Webster Groves was) most of us were totally surprised; our black classmate had to teach us how ordinary such discrimination was. Our class spent the rest of the day with our teachers talking it out and trying to find a way to respond, to make things different. I think we wrote a letter of protest.

As a sophomore at Webster College four years later, I encountered the same lunch counter discrimination, but by that time there were more options for response. I saw a bulletin board flier of an organization called CORE (Congress of Racial Equality) working to “open up” a lunch counter in Webster Groves. I joined the picket line. Naturally my grandfather, aunts and uncles, seeing me on the line as they drove down Webster’s main street, started calling my parents, “What is Eleanor doing!!??” And my father, equally upset, sat me down at the kitchen table to reason with me: “Eleanor, those sisters of yours are not going to let you join them if you get yourself arrested.” To which I replied, “Dad, they put me up to it; jail time would be my ticket in!” I felt a bit smug about my protesting and, of course, self-righteous. I was only vaguely aware that CORE’s main work in St. Louis at the time was the far more basic and dangerous work of fighting for equal housing. I did recognize that picketing in my own backyard for lunch counter freedom was a safe activity compared to what I had considered and fearfully declined, the invitation in 1961 to join the Freedom Riders on buses into the deep South.

I didn’t get arrested and I did join Loretto that fall, 1962. One of the first inspirational books I picked up was Michael Harrington’s The Other America. Once again, I was completely taken by surprise to read about the hidden poverty in my own St. Louis. Harrington’s point, that city planning had as its goal to make poverty invisible, resonated with my own experience. I believe this early novitiate reading oriented me to a lifetime of letting my eyes be opened. I accepted without question the lifestyle of public witness which we were being taught, witness to a practical faith that required action.

In the years that followed the novitiate all of us were challenged by questions about the Vietnam war. As a young sister back at Webster to finish my degree, I couldn’t see how our country could be wrong, but my sister-classmates were joining groups like Clergy Concerned. So, I organized a “Study-In” for the college—an interruption of ordinary studies so the college community could read and discuss critiques of the war. Again I was on television and my grandfather was calling my mother: “Is that Eleanor on TV?!!”

I marched several times against the war. By myself for one large demonstration in Washington in 1967, I remember being frightened by the National Guardsmen lining rooftops along Pennsylvania Avenue, and being careful not to get caught up in the throngs pressing forward to do civil disobedience. I never have “crossed the line” in a demonstration. But I love the story about another Loretto woman who was challenged by the policeman arresting her, “Sister, what would your superior think of this?” To which she replied, “You can ask her yourself, she’s right over there being arrested.”

Not only the war but lots of other social injustices caught my attention in the late 1960s and led me to stand up and protest, albeit in the safest ways. The farm workers of California were organizing boycotts of grapes as a way to pressure growers to the bargaining table. In Boston Massachusetts, where I was continuing my studies, I spent early morning hours picketing outside the wholesale fruit yards. Like many across the nation, in quiet protest I neither bought nor ate grapes for decades.

Years later, back in Boston for more study, I gathered signatures on a petition to Nestle’s to stop their sales of infant formula in third world countries (where the lack of safe water makes formula dangerous). Following the direction of an organizer, with whom I had been in the novitiate, I carried an ironing board on the trolley to Copley Square, set it up on the busy street corner, and spent several hours hawking for signatures!

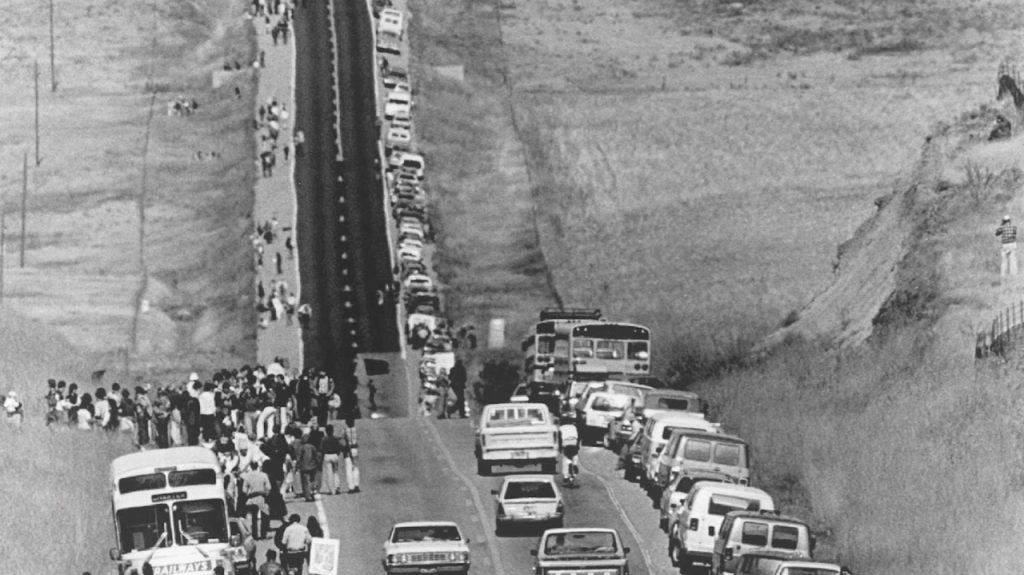

Protest and action were easy for me as a Loretto member, because so many other Lorettos were deeply involved. I had only to follow in their footsteps, literally, on the march or picket line or stand beside them at protest rallies. While visiting friends or doing Loretto work, I’ve joined in protesting nuclear armaments at Los Alamos, New Mexico, and in southern Colorado. There were many such rallies on the Plaza in Kansas City the years I lived there: against the first and the second Iraq wars, for the United Nations, against gun violence and violations of civil rights, for women’s rights. Some of these rallies were really large and were monitored by helicopters overhead. There were also marches. I was especially moved by the annual “Stations of the Cross,” organized by Maureen Smith, CoL, and others, to draw attention to places of human distress, need, and mistreatment along the streets of Kansas City.

Most recently, my protesting has been of the School of the Americas training center, where US military teach officers of other countries our well-developed tactics of torture and civil repression. Many Loretto sisters, comembers, students and friends joined the protests at Fort Benning, Georgia, in 1990 and subsequent years. I caught up with them only in 2014, when the connections between military repression and the flow of immigrants across our southern boarders were becoming painfully clear. My participation in the SOA protests expanded to include marching to the Stewart Detention Center at Lumpkin GA, near Ft. Benning.

Of course, I have marched many times with Lorettos and many other women in Washington—in the 70s for the ERA, in the 80s for women’s right to choose, and most recently in 2017 at the Women’s March.

What has all this marching and protesting meant? Is it effective? In what way? I haven’t paid attention to these questions in quite some time. Putting myself with like-minded marchers and protesters is so palpably the right thing to do, I push myself to do it. I’m basically timid; walking long distances doesn’t appeal to me; I feel anxious in big unruly crowds. But. Or rather, AND I often think of a conversation I had with Dorothy Day when I was young and she was old: I asked her, since much of the protesting she had done had not succeeded, what was the point. Her reply came quickly: I didn’t do it for the results, I did it because it was the right thing for me to do. I feel that’s what I’ve agreed to, to show up, walk shoulder to shoulder with others. To stand up and be counted. Often their hope increases mine.

Once I signed up for a march to end poverty. With a large group of labor and church leaders I rode overnight by bus from Kansas City to Washington. By time we reached D.C. I had a massive migraine. I spent the entire day in the medical tent, on a cot. Then I got on the bus back to Kansas City. What was the point? I was one more body swelling the community of those who believe in justice.

Nice work by a great lady.